A Deep Psychological Analysis

1. Understanding Extraverted Intuition as a Cognitive Function

Extraverted Intuition (often abbreviated as Ne) is one of the eight psychological functions identified by Carl Gustav Jung in his theory of psychological types. Unlike the more familiar conscious processes like thinking or feeling, intuition operates primarily below the threshold of awareness, surfacing as images, insights, and a sense of possibility that seems to arise spontaneously.

As a perceiving function, Ne does not evaluate or judge—it simply perceives patterns, relationships, and latent potentials in the external environment. It constantly scans for what could be, rather than what is. For the extraverted intuitive type, this is not a conscious choice but a natural psychological orientation: their mind is oriented toward the unfolding potential of external stimuli.

The experience of Ne can be compared to a radar sweeping the horizon—not focusing on any one object for too long, but rapidly detecting changes, connections, and new directions. This intuitive “sight” often manifests as visionary thinking, innovative ideas, or sudden realizations that seem to leap over logical steps.

What makes this function difficult to grasp is that it works without deliberate awareness. Even the intuitive individual may be unable to explain how they “know” something—they just know it, and often correctly. This can create a kind of mystique, even for themselves.

🔍 Analogy: If introverted intuition (Ni) is like an internal telescope, focusing on singular, deep insights, then extraverted intuition is like a kaleidoscope—constantly shifting, combining elements in novel ways, generating new possibilities through external engagement.

2. Intuition vs. Sensation: A Conflict of Perception

Jung emphasizes the natural opposition between Intuition and Sensation. Where Sensation (particularly extraverted Sensing) is grounded in immediate physical experience, Ne is future-oriented and relatively detached from the concrete.

This opposition creates internal tension when Ne is dominant: the more a person is tuned into emerging possibilities, the more they tend to suppress or ignore direct sensory input. Concrete sensory details are seen as distractions—noisy, literal, and often uninspiring. Sensation drags the intuitive person back into the now, while their psyche wants to roam freely toward the not-yet-real.

Yet, in practice, intuitive insights often use sensory impressions as raw material. An intuitive may notice a small, seemingly insignificant detail—like someone’s tone of voice, a shift in lighting, or a minor inconsistency—and from this generate a rich tapestry of potential meanings or predictions. These observations are selected not for their objective strength, but because they resonate with the intuitive’s unconscious framework.

Jung notes that such individuals may mistake these intuitive selections for genuine sensations, and even speak of them as “feelings” or “sensations.” However, their orientation is not to the sensory data itself, but to its symbolic or potential value.

This confusion can create communication difficulties with sensing types, who rely on objective, measurable input. What an intuitive values is not what “is,” but what “might become.”

3. The Role of Extraverted Intuition in Adaptation and Creativity

When Ne dominates a person’s personality structure, it becomes the primary tool of psychological adaptation. Unlike types who adapt by organizing facts (Thinking types) or maintaining harmony (Feeling types), the extraverted intuitive adapts by generating options, escaping confinement, and staying mobile—mentally, emotionally, and often physically.

This makes them ideally suited for creative, pioneering, and entrepreneurial roles. They are often the first to perceive opportunities where others see nothing. In blocked or stagnating systems—whether in business, politics, or personal relationships—they often act as catalysts for change, introducing new directions or frameworks.

However, Ne-dominant individuals also risk becoming chronically unsettled, because their inner stability depends on the continuous influx of novelty. Routine, predictability, or narrow systems of meaning feel suffocating to them. They may quickly disengage from environments or people that no longer offer a sense of possibility.

Jung vividly describes how normal life situations become “prisons” to the Ne type. What begins as exciting and full of promise can, once explored, become claustrophobic. They are driven to escape—sometimes destructively—simply to re-engage with that initial feeling of openness and emergence.

This creates a paradox: the more they pursue freedom and possibilities, the harder it becomes to commit or find lasting satisfaction.

4. The Extraverted Intuitive Personality: Motivations and Behavior

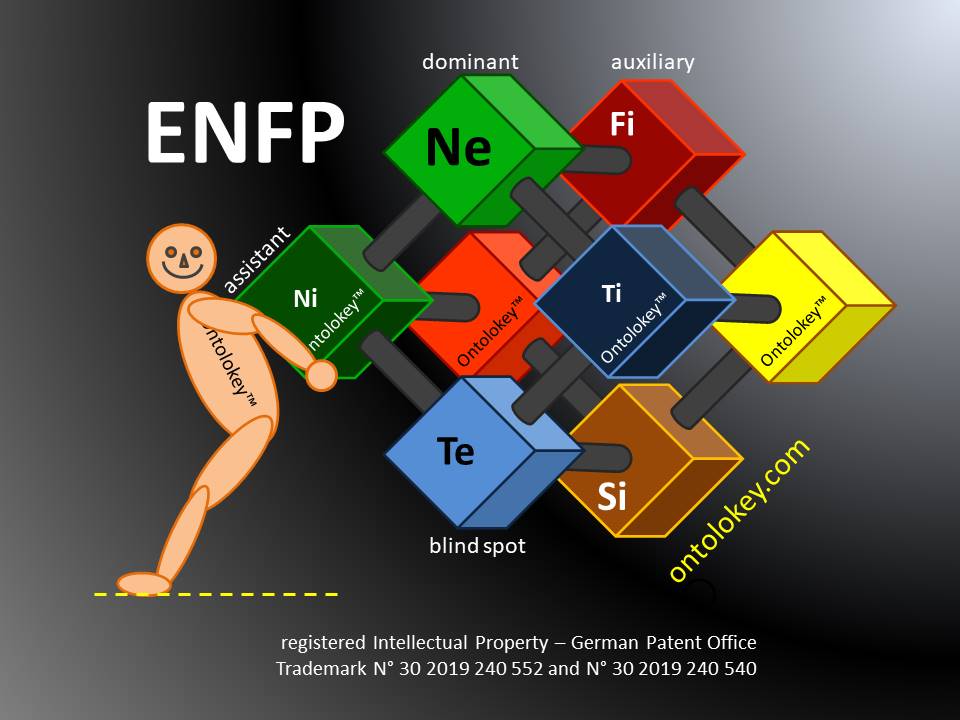

People who embody this type (often associated with ENTP and ENFP) exhibit a distinct psychological profile. Their primary motivation is possibility over permanence.

- They are highly responsive to emerging trends, sometimes even anticipating cultural or technological shifts before they’re widely visible.

- They are natural networkers, connecting people, ideas, and systems in surprising ways.

- They often experience life as a series of “turning points”, where every new opportunity feels definitive—until the next one arises.

They commit deeply and emotionally—but only to what is still unfolding. Once the outcome becomes predictable, their energy diminishes. From the outside, this can look like a lack of loyalty or depth. But internally, the intuitive feels a genuine loss of meaning.

Despite their enthusiasm, their judging functions—Thinking and Feeling—are often underdeveloped. This makes it difficult for them to evaluate or prioritize their many insights. Without this inner structure, they may leap into unwise ventures, misjudge others’ intentions, or spread themselves too thin.

⚠️ Common behaviors:

- Starting many projects, finishing few

- Rapid career or relationship changes

- Difficulty with repetition or routine

- Resisting commitment due to fear of “missing out” on something better

5. Moral Framework and Social Challenges

Because they are not primarily guided by logic or shared emotional values, extraverted intuitives often develop a personal moral code based on authenticity to their vision. Their ethical compass is oriented not toward social norms, but toward staying true to what they “see” intuitively.

This can make them appear:

- Unreliable or impulsive

- Disrespectful of tradition

- Opportunistic or emotionally distant

But their behavior is rarely malicious. The intuitive type experiences a moral imperative to follow the vision, even when it conflicts with obligations or past choices. They value potential over consistency.

Still, this orientation can cause real harm in relationships, institutions, or communities that require stability, patience, or predictability. Their enthusiasm may inspire others to follow, only to be left behind when the intuitive moves on.

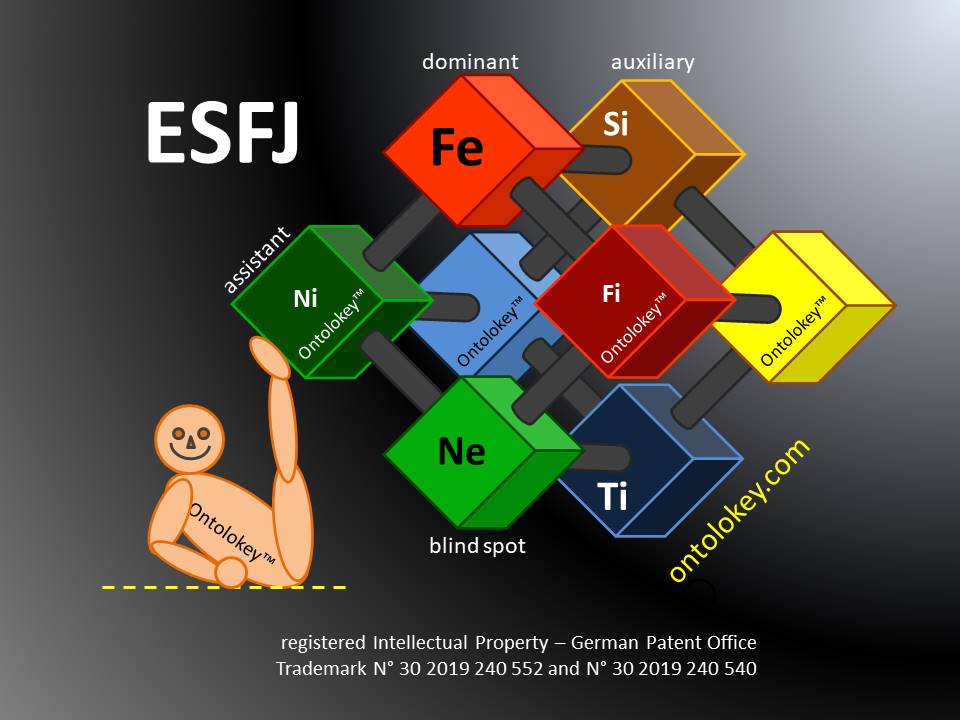

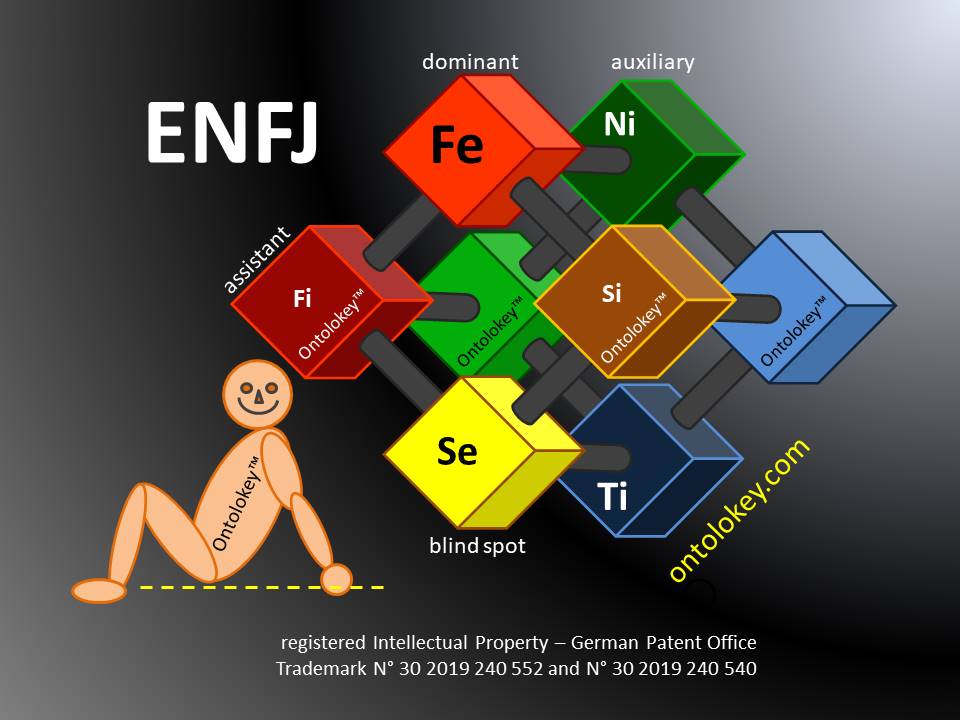

The challenge for the Ne-dominant person is to develop auxiliary judging functions (typically Introverted Feeling or Introverted Thinking) to provide grounding, discernment, and a sense of responsibility.

6. Unconscious Compensation and Psychological Risk

When the extraverted intuitive suppresses their lesser-used functions—especially Sensation, Thinking, and Feeling—these can manifest in the unconscious in distorted or neurotic forms.

According to Jung, the intuitive’s inferior function (often Sensation) can emerge as:

- Somatic anxiety

- Hypochondria

- Obsession with bodily functions

- Sudden, irrational emotional attachments

This happens because the intuitive has neglected the real, physical, and emotional content of life, focusing instead on abstract potential. Eventually, the psyche demands compensation. The more the intuitive tries to float above reality, the more forcefully the unconscious anchors them with irrational fears or compulsions.

These symptoms often take symbolic form—phantasms of sickness, misfortune, or overwhelming needs—which feel out of sync with their usual detachment. Jung even notes that Ne types may become entangled in obsessive relationships with people who evoke repressed emotional or sensory content.

Such fixations can feel deeply irrational and humiliating to the intuitive type, yet they are symptoms of the psyche trying to reintegrate neglected functions.

🧠 Therapeutic goal: Help the intuitive type reconnect with the concrete world—not by extinguishing their gift for vision, but by supporting the development of Feeling, Thinking, and Sensation in a healthy, conscious way.

7. Cultural and Social Value of the Ne Type

Despite their challenges, extraverted intuitives play a crucial cultural role. They are:

- Early adopters and change-makers

- Advocates for innovation and minority viewpoints

- Visionaries who see beyond established paradigms

In politics, business, and social movements, they can initiate radical change when others cling to the status quo. When morally grounded, they uplift entire communities by empowering others and giving voice to the future.

Yet, to fulfill this role responsibly, they must learn inner structure—the ability to evaluate their insights, care for those affected by their actions, and stay long enough to build what they begin.

Only then can they reap the harvest of the many seeds they sow.

✅ Summary

The extraverted intuitive type is driven by a powerful, unconscious orientation toward future possibilities. They perceive hidden potentials in people, systems, and environments and are compelled to act on what others cannot yet see.

But this gift comes with the risk of instability, escapism, and emotional detachment. Without grounding in other psychological functions, the intuitive may sacrifice substance for the thrill of discovery, leaving behind unfinished projects and relationships.

Their challenge is to integrate inner judgment and grounded perception, allowing their vision to take root and bear lasting fruit.