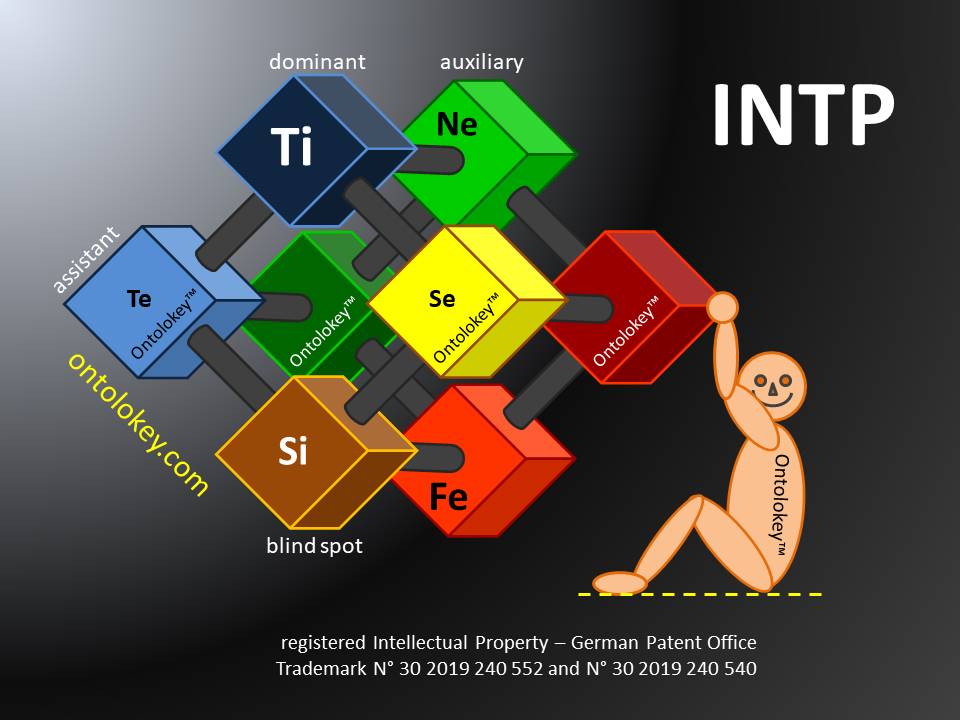

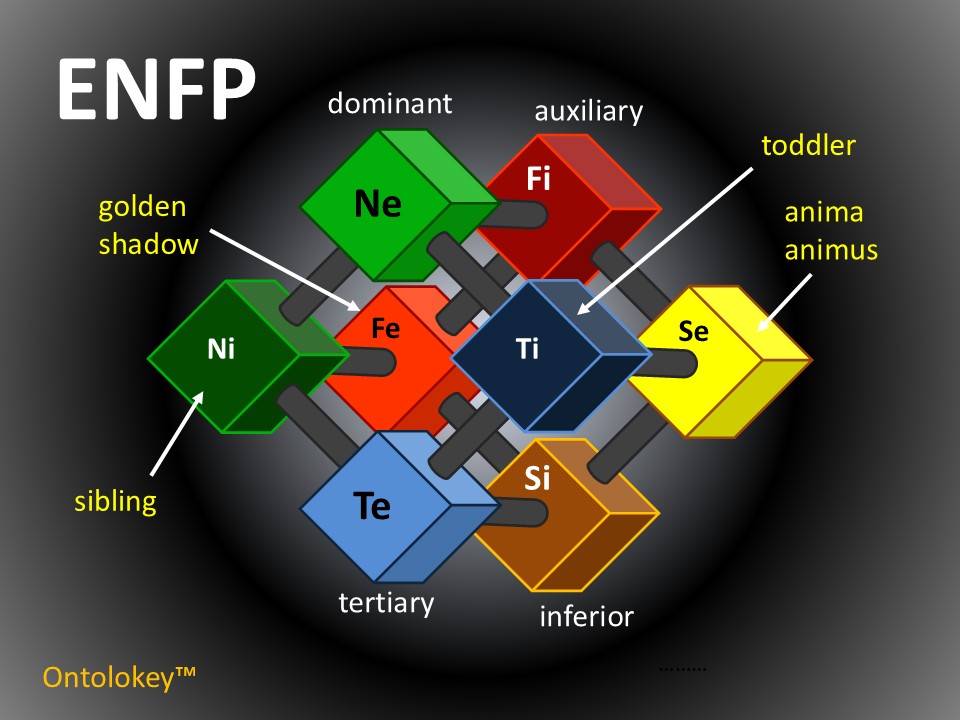

From the very beginning, thinking in all directions, rarely believing in boundaries, always seeking the next possible thing: This is perhaps the most accurate description of the ENFP – the extraverted intuitive feeler with an irrational base structure. Yet what may seem like a fleeting creative spark reveals itself, through the Ontolokey model, as a complex and multi-layered personality core, in which all eight psychological functions – both conscious and unconscious – stand in finely tuned dynamic relation to one another.

1. Extraverted Intuition (Ne) – The Gaze Beyond the Horizon

The ENFP’s dominant function is Extraverted Intuition (Ne) – a psychological radar constantly scanning for possibilities, patterns, ideas, connections, meanings, and future scenarios. Ne is the “camera” in the Ontolokey cube, perceiving the world not as a set of facts, but as a realm of potential.

Individuals with dominant Ne possess a natural ability to think outside the box. Their attention is future-oriented, associative, idea-rich. This makes the ENFP a visionary, an innovative connector, one who enjoys simultaneously imagining multiple realities. Boundaries are flexible, even negotiable.

Other typologies often describe the ENFP as charismatic, enthusiastic, and values-driven. But in the Ontolokey framework, Ne is not just dominant – it is in constant interaction with three opposing introverted functions, forming what the model calls a tripod.

2. Fi – Introverted Feeling: Inner Ethics as a Stabilizer

Directly linked to Ne via a cube edge is the auxiliary function: Introverted Feeling (Fi). It forms the ENFP’s internal ethical compass – quiet but deeply felt. While Ne freely associates, Fi asks: “Does this resonate with my values?”

Fi does not speak loudly, but it does speak firmly. It provides inner grounding and moral coherence. It is the quiet depth behind the ENFP’s vibrant idea engine. Fi also plays a key role in the ENFP’s Persona, which often appears ISFP-like – creative, aesthetically sensitive, and emotionally centered.

The dynamic tension between Ne and Fi – between outer exploration and inner alignment – is central to the ENFP’s psychological development. The movable slider between these two functions reflects this balance: When Ne dominates and Fi is underutilized, idealism may become unmoored; when Fi takes over, creative inhibition can result.

3. Ni – The Sibling Function: Introverted Intuition as Mirror

Introverted Intuition (Ni) is the “sibling” function, also connected to Ne. It focuses not on external possibilities but on deep internal insights and symbolic meaning.

For the ENFP, Ni often remains ambivalent or underdeveloped. The slider between Ne and Ni shows the individual’s capacity not just to explore ideas outwardly, but to delve inward, to intuit complex internal truths. As Ni becomes more integrated, the ENFP gains access to focused vision beyond mere associative potential.

4. Ti – The Toddler Function: Introverted Thinking as Developmental Key

The Toddler function, still in early development, is the ENFP’s Introverted Thinking (Ti). It stands for logical analysis, internal structure, and precise categorization – abilities that initially challenge the ENFP but are essential to their growth.

In early stages, Ti often appears fragmented or impulsive – thinking may be erratic or lacking in depth. But as this function matures, it empowers the ENFP to critically evaluate, structure, and clearly express their ideas – transforming chaotic inspiration into actionable strategy.

5. Si – The Inferior Function: Introverted Sensing as a Growth Challenge

The greatest growth challenge lies in the inferior function: Introverted Sensing (Si), which represents tradition, stability, bodily awareness, and memory.

For the forward-looking ENFP, Si can feel like a restriction – slow, rule-based, past-oriented. Yet it is essential as a counterbalance to the expansive Ne. Underdeveloped Si often results in disorganization, poor stress resilience, and a disconnection from the body. The development of Si leads to grounding, patience, and inner calm.

6. Se – The Anima: Extraverted Sensing as Soul Figure

In Jungian terms, the Anima (Extraverted Sensing – Se) is the soul figure – the instinctive, inner personality. For the ENFP, Se embodies direct sensory experience, something both foreign and deeply alluring.

Se lives in the moment – in touch, color, taste, sound, and physical vitality. It is spontaneous, vivid, and present. ENFPs often project this archetype onto others: people who dance, live boldly, travel freely, enjoy the here and now. Integration of Se means reclaiming one’s own capacity for embodiment and sensual engagement.

7. Te – The Tertiary Function: Extraverted Thinking as the Inner Child

Extraverted Thinking (Te), the tertiary function, is archaic, childlike, and impulsive in the ENFP. It governs external structure, results-oriented action, and assertiveness – areas that often emerge in fits and starts.

In early development, Te shows up in passionate arguments or overzealous campaigns. With maturity, it becomes a tool for organizing ideas and realizing visions – not for domination, but for execution. It gives the ENFP’s ideals a practical pathway into the world.

8. Fe – The Golden Shadow: Extraverted Feeling as Hidden Potential

The Golden Shadow of the ENFP is Extraverted Feeling (Fe) – the capacity to harmonize, mediate, and lead emotionally. This potential lies unconsciously dormant – not because it is bad, but because it doesn’t fit the self-image.

ENFPs often project Fe onto admired leaders, emotional nurturers, or charismatic influencers. Integrating Fe means recognizing one’s latent power to guide and unify, not just through ideas, but through emotional resonance. This is where leadership becomes not just possible, but authentic.

9. Integration & Balance – The Art of the Sliders

The 12 sliders in the Ontolokey cube allow nuanced self-assessment. They illustrate dynamic tensions such as:

- Ti–Ne: logic vs. ideation

- Fi–Fe: inner values vs. social values

- Se–Si: present-moment awareness vs. memory-based stability

For the ENFP, three sliders in particular – the tripod – are key to personal growth:

- Ne–Fi: creativity and ethics

- Ne–Ni: openness and depth

- Ne–Ti: vision and clarity

Development occurs not through over-reliance on strengths, but through intentional balancing and conscious use of all functions.

10. Conclusion – The ENFP as an Integrated Self

Ontolokey shows us that no psychological function exists in isolation. The ENFP is not just an idea machine – they are a dynamic center of energetic movement, suspended between idealism, emotional depth, rational evolution, and sensory yearning.

True maturity arises when the ENFP integrates not only what they know, but what they’ve long ignored: presence (Se), structure (Si), leadership (Te), and social resonance (Fe).

In a world increasingly polarized, the mature ENFP – visionary, ethical, differentiated, embodied – can become a bridge between worlds.