Holding the Psyche: The Ontolokey Cube and the Geometry of Individuation

In the field of depth psychology, few ideas have resonated as powerfully and persistently as Carl Gustav Jung’s concept of individuation—the lifelong process by which a person becomes psychologically whole. Jung’s psychological model is rich with symbolic dimensions, yet remains grounded in the tension between the conscious and the unconscious, the known and the not-yet-known. While his typology of psychological functions has found practical application in systems such as the MBTI and Socionics, these frameworks are often represented in two-dimensional diagrams or categorical charts that fail to express the fluid, embodied nature of psychic life.

The Ontolokey Cube emerges as a compelling alternative: a three-dimensional, tactile, and symbolically informed object that transforms the theory of psychological functions into something one can hold, turn, examine, and—quite literally—grasp. The cube is not a metaphor, nor is it a mere teaching aid. It is a physical instrument designed to model the architecture of personality, to visualize the interplay of conscious and unconscious tendencies, and to support the unfolding process of individuation. In its structure, materials, and the symbolic logic that governs its form, it invites its user to contemplate the psyche as a living system in motion.

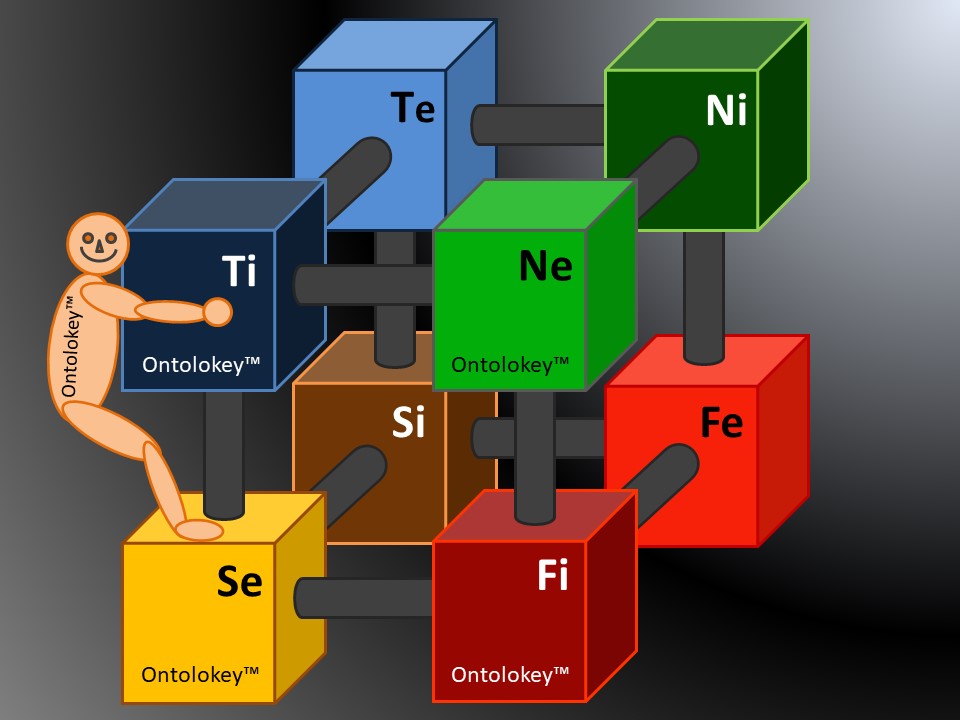

Constructed as a standard cube, the Ontolokey Cube comprises eight corners, each representing one of the eight Jungian psychological functions: Thinking (introverted and extraverted), Feeling (introverted and extraverted), Sensing (introverted and extraverted), and Intuition (introverted and extraverted). These corners are connected by twelve edges—solid rods that house movable sliders. Each slider visually expresses the dynamic balance between two functions. For example, the edge connecting introverted thinking (Ti) and extraverted thinking (Te) carries a small disc that can be moved to indicate how much the individual draws on one versus the other. All twelve sliders can be adjusted, allowing the cube to serve as a kind of “dialectical compass” for mapping psychological balance.

Unlike flat charts or typological boxes, the cube allows for physical interaction. The user can rotate the object, adjust sliders, and view the configuration from different angles. This engagement of the body—the hand, the eye, the sensation of motion—parallels the psychological movements it seeks to represent. The cube becomes a mirror of inner life, one that makes space for both structure and transformation.

One of the central innovations of the model lies in how it organizes the functional system around triads. Each corner is not isolated but forms a kind of psychological tripod, consisting of the dominant function and three supporting ones: an auxiliary function that reinforces it, a sibling function that shares its mode (introverted or extraverted), and a so-called toddler function, which is psychologically present but often underdeveloped. These triads reflect the interdependence of psychic components: no function stands entirely alone, and the efficacy of the dominant mode depends in part on the flexibility and integrity of its support system.

If, for instance, a person’s dominant function is introverted thinking (Ti), this will be positioned on the cube as the dark blue corner. Connected to it via three edges are extraverted intuition (Ne), extraverted sensing (Se), and extraverted thinking (Te). These become the tripod legs that stabilize the Ti function. The metaphor is that of a camera mounted on a tripod: Ti is the lens through which the person primarily views the world, but that lens depends on three stabilizing supports to operate clearly. This concept echoes elements of Socionics Model A and other function-based systems that explore relational dynamics between cognitive modes.

The cube also incorporates a polar structure, reflecting Jung’s insight into the psyche’s tendency to move between opposites. The surface of the cube is divided into two opposing faces: one contains the spontaneous functions (Se, Ne, Ti, Fi), referred to as the P-group, and the other the scheduling functions (Te, Fe, Ni, Si), the J-group. The edges connecting these opposing groups—Ne to Ni, Fi to Fe, and so on—represent key psychological tensions, such as the one between internal perception and external judgment, or between sensory input and intuitive abstraction. The position of each slider along these axes offers a concrete visualization of where a person currently resides in this intrapsychic dialogue.

Yet it is not only the conscious mind that the cube seeks to reflect. Just as Jungian psychology insists on the necessity of integrating unconscious contents, the Ontolokey Cube builds in a space for the “Shadow”—that dimension of the psyche which holds suppressed, neglected, or unrecognized qualities. In the model, the function opposite to the dominant is understood as inferior: underdeveloped, perhaps avoided, yet crucial to the process of growth. Around this inferior function form three further symbolic supports: the Anima or Animus (the gendered psychological other), the Golden Shadow (repressed talents or potential), and the Tertiary function (often undeveloped but psychologically accessible). This arrangement constitutes the “shadow tripod”—a structural counterpoint to the conscious tripod of the dominant function.

When the cube is viewed or rotated from the opposite side, these shadow functions come into view. Their placement and interrelationship represent the latent energies of the personality, waiting to be encountered, integrated, or transformed. These dynamics become particularly vivid in one of the most symbolically charged aspects of the cube: its ability to unfold.

Unfolding Structure, Integrating Shadow

One of the most revealing aspects of the Ontolokey Cube is its capacity to unfold. What initially presents itself as a self-contained geometric solid can, through a simple transformation, be laid open into a cross-like figure. This gesture is not merely mechanical. It is symbolic, echoing the archetypal process of inner revelation and reconfiguration—a movement from containment to integration.

When unfolded, the cube reveals its eight vertices on a two-dimensional plane, arranged in the form of a cross with a clear vertical and horizontal axis. The vertical axis of the cross shows from bottom to top the 4 psychological functions, dominant function, auxiliary function, inferior and tertiary function. The horizontal axis shows the 4 psychological functions Sibling, Golden Shadow, Anima/Animus and Toddler. This layout mirrors the spiritual and alchemical significance of the cross in Jungian symbolism: a symbol of the Self, the tension of opposites, and the path of wholeness that reconciles them. In this new configuration, the eight functions—no longer hidden behind edges or confined by three-dimensional orientation—become fully visible. Each takes its place on the “map” of the psyche.

At the bottom of the cross lies the dominant function, which can now be seen in direct relationship to all others. Above it stands the auxiliary function. The horizontal arms stretch towards the sibling and Golden Shadow on one side and the anima/animus and the toddler function on the other. The upper part of the cross consists of the inferior and the tertiary functions. The four external endpoints of the cross are the dominant function at the bottom, the tertiary function at the top as the head, the sibling function is the one hand at the end of the horizontal arm, and the toddler function is the other hand of the other horizontal arm. This arrangement exposes not only the orientation of conscious functions but also the often-neglected architecture of the unconscious: the functions that lie latent, repressed, or only partially accessible. The cross thus becomes a mandala of personality—a diagram of psychic potential, complexity, and integration.

Such a transformation from cube to cross invites reflection on the teleological nature of individuation. Jung emphasized that psychological development is not a linear accumulation of traits but a spiral movement toward synthesis. The Ontolokey Cube, in its folded and unfolded forms, illustrates this: from a compact configuration that privileges dominant functions, toward an open form in which the shadow and the unconscious are brought into view. What was previously hidden—functionally and symbolically—can now be encountered consciously.

In therapeutic or coaching contexts, this unfolding gesture can be staged as a ritual of insight. A practitioner might guide a client through the process: first identifying the dominant tripod and its stabilizers, then rotating the cube to examine the shadow system, and finally unfolding the structure to place all elements into a unified field. In doing so, the practitioner does not interpret the client into a fixed category but rather facilitates a living conversation between function, form, and feeling.

This embodied interaction opens pathways for reflection, recognition, and recalibration. For example, a client may realize that their overidentification with extraverted thinking (Te) has left little room for introverted feeling (Fi), which appears across the cube as its neglected counterpart. Or they may begin to see how their intuitive capacities (Ne/Ni) have grown at the expense of grounded sensory input (Se/Si). These insights are not delivered from above but emerge from within the act of handling, turning, and unfolding.

In this sense, the Ontolokey Cube becomes a participatory diagnostic tool. It respects the fluidity of type, the nuance of development, and the multiplicity of psychic voice. Rather than categorizing, it reveals orientation and tension. Rather than closing identity, it opens space for evolution.

Moreover, the cube’s geometry allows for symbolic identification with mythic and archetypal figures—a form of active imagination. When a user sees their personality mapped in this way, they may begin to recognize themselves not just as a “type,” but as a traveler within a symbolic terrain. The dominant tripod may evoke the clarity of Athena or the rigor of Hermes; the shadow tripod may whisper the forgotten stories of Hades or Persephone. The cube becomes a theater of archetypes, staging the drama of integration in miniature.

Such use draws directly from Jung’s understanding of myth as a mirror of individuation. In classical mythology, figures like Odysseus, Parzival, or Psyche undergo journeys that mirror the dynamic of the cube: a departure into unconscious material, an encounter with shadow, and a return that reintegrates new awareness. The Ontolokey Cube, by modeling these inner movements in space, becomes not just a tool for self-awareness, but a compass for personal myth.

Its educational applications are equally promising. In teaching settings, the cube can be used to introduce Jungian functions not as dry abstractions but as spatial, relational elements. Students can explore the difference between extraverted sensing and introverted intuition by observing their placement and orientation. They can discuss the energies of the J and P planes by physically turning the object. In group contexts, different cubes can be used to compare typologies, to explore complementarity, and to mediate interpersonal conflict through structural clarity.

What makes the cube especially valuable in such contexts is its refusal to oversimplify. It affirms complexity while offering tools to navigate it. It encourages users to think in terms of balance, support, and transformation—not labels. And by engaging the body, it helps to anchor psychological insight in experience, making reflection something that can be touched, not just theorized.

The final significance of the Ontolokey Cube lies in its symbolic neutrality. It does not promote one type over another, nor does it pathologize shadow content. Instead, it affirms that each psyche has its own unique geometry, its own pathway through the field of functions. By holding the cube, turning it, unfolding it, and returning it to form, the individual symbolically enacts the rhythm of individuation itself: from differentiation, to encounter, to integration.

In a culture increasingly prone to reductive identity typing and static categories, the Ontolokey Cube offers something rare: a model that is structural but dynamic, psychological but embodied, symbolic but usable. It reminds us that personality is not a checklist—it is a geometry of becoming.

Conclusion: From Structure to Symbol, From Self to Whole

The Ontolokey Cube is, in the final analysis, more than a tool for typological mapping. It is a model of possibility—possibility not only for understanding oneself more deeply, but for entering into an ongoing relationship with the psyche as a living system. Where standard personality tests draw boundaries, the cube draws connections. Where charts classify, the cube invites exploration.

Its power lies in its form. In its three-dimensionality, the cube resists the flattening tendencies of digital and conceptual models. In its tactility, it restores the role of the hand in psychological knowing—reminding us that the act of grasping is both physical and cognitive. In its symbolic unfolding, it gives spatial expression to the temporal rhythm of individuation: opening, encountering, integrating, returning.

Jung often emphasized that psychological insight must become embodied to be transformative. The cube makes this principle tangible. It is not merely an object of analysis, but a surface for projection, a mirror for myth, a map for orientation. As such, it serves not only individuals but communities: therapists, teachers, researchers, artists, and coaches who seek to foster the conditions for inner dialogue.

At a cultural level, the Ontolokey Cube may also be read as a response to a deep modern hunger—for structure without rigidity, for identity without fixity, for tools that support development rather than diagnosis. It offers an image of the psyche that is stable yet dynamic, structured yet open, symbolic yet functional. In doing so, it aligns with a broader movement in psychology and the humanities: toward systems that honor complexity, respect embodiment, and recognize the irreducible depth of the human person.

What the user holds in their hands, then, is not just a cube—it is a gesture toward wholeness. A model of psyche that can be touched, turned, unfolded. A reminder that the journey toward the Self does not happen in abstraction, but in the concrete movements of attention, reflection, and symbolic play.

To hold the Ontolokey Cube is to hold a question:

Who am I becoming—now, here, in this form?

And that question, held in both mind and hand, is the beginning of individuation.

About the Name “Ontolokey”

The name Ontolokey is a synthesis of two words: Ontology—the philosophical study of being—and Key. It represents a “key to being,” a gateway to understanding the psychological and spiritual essence of the human person. Ontolokey serves as an interpretative tool for unlocking the symbolic and alchemical language found in works such as the Rosarium Philosophorum, Azoth, and Lambspring, which were also explored by C.G. Jung. Without the key provided by Ontolokey, a proper understanding of these texts and images remains incomplete. Thus, the name underscores its central purpose: to offer a key to the psychological alchemy described by thinkers like Jung and Hegel—a path toward comprehending the deeper nature of being itself.

Trademark Registration

Ontolokey is a registered trademark, officially recorded in the register of the German Patent and Trademark Office (Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt, DPMA) under registration number 302019240552. The protection period of the trademark commenced on the filing date and extends until December 16, 2029. In accordance with Section 47 of the German Trademark Act (Markengesetz), this protection may be renewed for additional ten-year periods. Furthermore, Ontolokey is registered as a word mark under registration number 302019240540, ensuring comprehensive legal protection of both the name and its conceptual integrity.

Leave a comment