Understanding Introverted Feeling (Fi): A Core Psychological Function

Introverted Feeling (abbreviated as Fi) is one of the eight cognitive functions identified by Carl Gustav Jung in his theory of psychological types. As a judging function, Fi evaluates experiences, people, and situations based on deeply personal, internal value systems rather than objective or socially agreed-upon standards.

While Extraverted Feeling (Fe) organizes emotional responses around collective values—such as harmony, etiquette, or the emotional needs of a group—Fi filters emotion through individual authenticity and inner resonance. It seeks emotional truth, not consensus. Therefore, Fi often prioritizes what “feels right” internally over what is expected externally.

Jung considered Fi to be profoundly subjective, shaped by the unique emotional landscape of the individual. This subjectivity grants Fi moral depth, but also makes it inaccessible and easily misunderstood by others.

The Elusive Nature of Fi: Why It’s Hard to Recognize

Fi rarely manifests in visible or socially expected emotional expressions. Its evaluations are intensely private and often nonverbal, making it one of the most opaque and misunderstood psychological functions. Jung described Fi as “difficult to describe intellectually,” and noted that it often withdraws from the outside world rather than engaging with it directly.

This can make Fi types appear emotionally flat, cold, or indifferent—especially to those with extraverted feeling (Fe) preferences. However, this perception stems from a fundamental misreading: Fi isn’t emotionless; it’s simply inward-facing. Its intensity increases with depth, not breadth. The more profound the emotional experience, the less likely it is to be shared outwardly.

Moreover, Fi types often underreport or hide their emotional reactions, not because they lack feeling, but because they protect it like something sacred. This protectiveness can create an aura of mystery or emotional detachment, especially in situations where emotional conformity is expected.

Fi’s Relationship to Archetypal Ideals and Inner Imagery

Jung highlighted that introverted feeling is frequently guided by archetypal images or emotional ideals—unconscious mental templates that represent universal emotional truths (e.g., the nurturing mother, the innocent child, the noble warrior). Fi seeks to align personal experience with these deeply symbolic emotional patterns, which often operate outside of conscious awareness.

Rather than adapting to reality, Fi attempts to elevate reality to match these internal standards. This is a constructive but also frustrating process, as the external world almost never lives up to the inner emotional vision. As a result, Fi can glide over real-world people and situations with disinterest or even disdain—not because they are unworthy, but because they fail to resonate with the person’s internal emotional truth.

This tendency to pursue an inner emotional ideal rather than connect emotionally to actual people or objects contributes to Fi’s reputation for aloofness. It can also cause dissatisfaction, existential loneliness, and emotional longing that is hard to articulate or resolve.

Emotional Reserve and Self-Containment

Fi-dominant individuals (especially in Jung’s time, more frequently observed in women) tend to display a calm, self-contained emotional attitude. They often come across as reserved, introspective, and socially neutral, avoiding outward demonstrations of emotion or attempts to emotionally influence others.

This restraint is not an absence of emotional energy but a form of emotional self-discipline. These individuals often resist overt passion, melodrama, or excessive sentimentality—whether in themselves or others. Strong emotional displays from others may be met with detachment or even discomfort, unless the emotional expression taps into a shared internal symbol or feeling that resonates unconsciously.

This “quiet passion” gives Fi types a certain emotional dignity, but also renders them susceptible to being misread. Many are unfairly labeled as cold or distant, when in fact they are simply deeply selective and cautious about emotional exposure.

The Intensity and Selectivity of Fi Emotions

One hallmark of introverted feeling is its emotional intensity, even if it is not externally visible. Fi doesn’t seek broad emotional involvement, but rather deep, personal resonance. An Fi person may be unmoved by a large-scale tragedy, yet emotionally devastated by a single, symbolically meaningful detail.

Fi prefers emotional fidelity over emotional efficiency. For example, where extraverted feeling might express compassion through helpful action or comforting words, Fi may be emotionally frozen—consumed by an inner response that defies articulation.

Because of this inward processing, Fi can at times seem paralytic—especially when faced with moral dilemmas or emotionally complex situations. Yet when Fi does act, it may do so with surprising force and commitment, often in ways that appear heroic or sacrificial, driven not by external reward but by an internal imperative to be true to oneself.

Misinterpretation, Projection, and Isolation

Because Fi processes feelings privately and in depth, it is often at odds with social norms. Many Fi users have experienced misunderstanding, social friction, or alienation because their emotional responses are not shared or explained in conventional ways.

Fi types may experience the painful sense that others “don’t understand” them or that their emotional world is too complex or sacred to be shared. Over time, this can lead to emotional withdrawal, suspicion, or even contempt toward those perceived as shallow, emotionally manipulative, or morally inconsistent.

If this process is internalized too strongly, Fi can begin projecting mistrust or moral judgment onto others—seeing them as impure, self-serving, or emotionally dishonest. This tendency can contribute to social isolation, emotional rigidity, and—if unbalanced—neurotic symptoms.

The Archetypal Power and Magnetism of Fi

One of the most striking features of Fi is its archetypal emotional power—a kind of quiet intensity that exerts a gravitational pull on others, especially on individuals who lack this inner connection themselves. Jung noted that this often has a mystical or even spiritual quality, giving Fi-dominant individuals an aura of emotional wisdom or unspoken authority.

This power arises not from charisma or social influence but from a profound attunement to inner truths. In a healthy individual, this can create a grounding emotional presence; in an unbalanced one, it can evolve into emotional manipulation, spiritual superiority, or even tyranny—especially when the ego identifies too closely with these unconscious emotional archetypes.

The Shadow Side of Fi: Ego, Sentimentality, and Neurosis

When Fi becomes inflated by ego, it no longer serves inner truth, but starts to protect or aggrandize the self. This leads to a distorted version of Fi: emotionally hypersensitive, controlling, judgmental, and obsessed with being seen as morally superior or “special.”

In this state, Fi may produce behaviors such as:

- Sentimentality that masks emotional control

- Emotional blackmail or silent treatment

- Paranoia about how others “really” feel

- Obsessive focus on betrayal, rejection, or injustice

In Jungian terms, this descent reflects a breakdown of integration between the feeling function and the unconscious. As Fi becomes consumed with self-concern, its compensating opposite—extraverted thinking (Te)—may assert itself in distorted ways: planning, scheming, suspecting others of manipulation, or micromanaging relationships.

This can manifest as neurotic defenses, including social withdrawal, psychosomatic symptoms, or intense rivalries based on imagined slights. Jung linked this condition more with neurasthenia than hysteria: exhaustion, internal tension, and spiritual collapse.

Fi and Gender: Jung’s Cultural Context

Jung’s original writing associated dominant Fi more commonly with women—particularly those of an introverted, sensitive, and emotionally reserved disposition. He emphasized their stillness, depth, and a tendency to live through inner emotional worlds rather than outwardly directed ambitions.

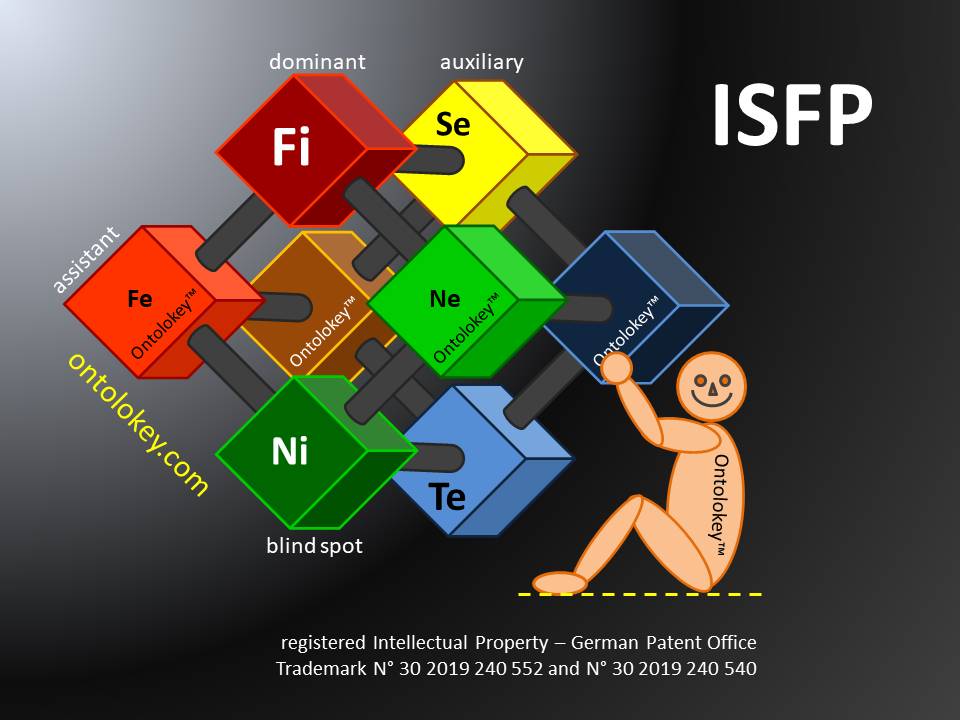

However, it’s important to modernize this view: Fi is not gendered. Many men today—especially those of the INFP or ISFP MBTI types—demonstrate dominant Fi. What Jung observed culturally in women was likely influenced by social roles and expectations of his time, which restricted emotional expression in men and action in women.

The essence of Fi remains consistent across gender: a deeply personal relationship to values, a tendency toward emotional integrity, and a preference for quiet authenticity over external validation.

Integration and Growth: The Path of Fi Development

For Fi to be psychologically healthy and integrated, it must remain rooted in values larger than the ego. As long as the individual recognizes that their emotional truths point toward something beyond the self, Fi becomes a source of moral insight, integrity, and human depth.

This requires:

- Openness to other people’s truths (without abandoning one’s own)

- Finding creative or symbolic outlets for emotional expression (e.g., art, writing, spirituality)

- Balancing Fi with its opposite function (Extraverted Thinking), to bring clarity, action, and structure to emotional conviction

When integrated, Fi offers something rare and precious: a capacity for quiet, authentic compassion that neither demands attention nor depends on external approval. It is the emotional conscience of the psyche—a voice that whispers, not shouts, but always tells the truth.

Leave a comment